Indian King of the Baggers

Chuckwalla Raceway is my local track in California. It’s a bit of a goat track, but it’s got some decently quick bends and elevation changes that always keep you on your toes.

Conservatively, I’d say I’ve completed 3000 laps here over the last eight years, way more than any other racetrack I’ve ridden. I know this place like the back of my hand, but on the Mission Foods/S&S Cycle/Indian Challenger of Tyler O’Hara, I may as well be on Mars.

O’Hara’s beastly bagger sounds like one half of a NASCAR and goes almost as fast, but that’s not the scary bit. It’s the way the chassis moves under me like it’s permanently got a teeny tiny spray of oil on the street-spec Dunlop Sportmax Q4 rear tyre—you know, just enough to keep you on your toes but not enough to throw you down the road—that has me worried.

“It’s like the bike has a split personality,” O’Hara tells me. “You can ride the bike hard and shift hard and accelerate hard, but you have to be real careful with it. She likes to go fast, but there’s a method to getting her to go fast.”

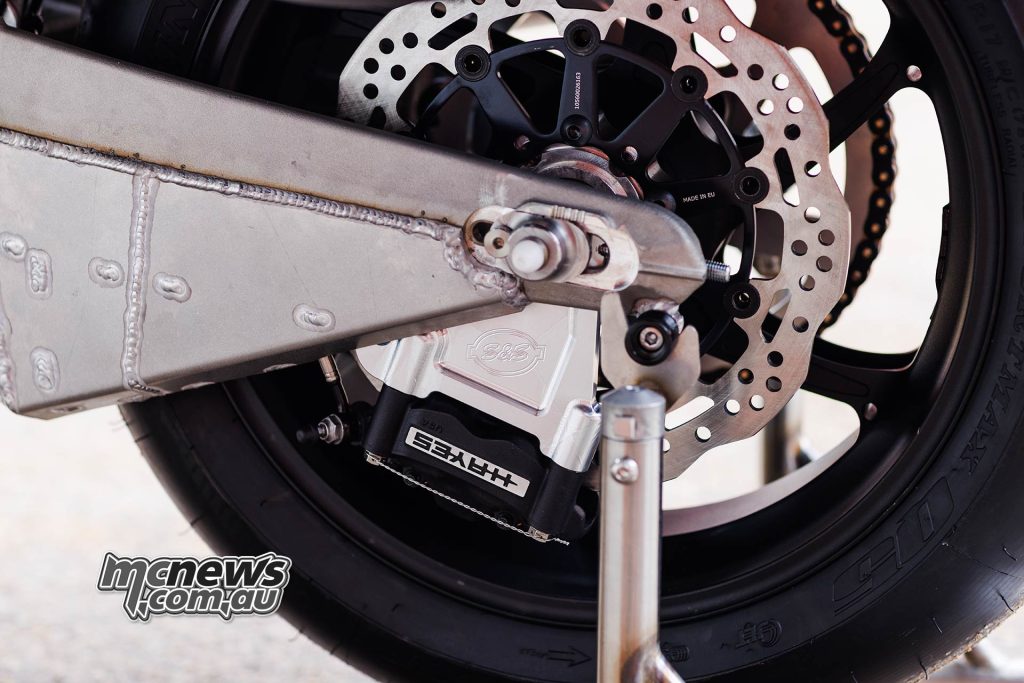

The secret to making it all work is to liberally use the thumb-operated rear brake, first to actually help slow the 275 kg maroon monster but secondly, and more importantly, to help control the rebound of the rear suspension as the throttle is reapplied so you can keep everything on its intended path.

“You absolutely have to use the rear brake,” O’Hara says. “If you don’t, it makes it very difficult to get the bike to turn tight, and you spend too much time between braking and accelerating. Plus, you can use the rear to damp out the chassis flex, which has been an issue with our bike.”

Reefing the ride-by-wire throttle open on a bagger the likes of O’Hara’s American-as-f**k 1835cc V-twin racer requires a mixture of brute aggression and finesse to get all that torque to the ground.

The frame, modified as much as the MotoAmerica King of The Baggers rules will allow (which is basically not at all), flexes with the kind of willingness more akin to a 1983 Honda VF1000R, the front, centre and rear of the motorcycle squirming and snaking its way around Chuckwalla with me more or less just a passenger.

“By rule, we can’t really modify any of the chassis parts,” says S&S’s Chief Engineer, Jeff Bailey, the man largely responsible for creating, maintaining and improving O’Hara’s and team-mate Jeremy McWilliams’ racebikes. “We did get an allowance from MotoAmerica to machine a bit off the front frame spars for ground clearance, but that’s really the only modification that we do to the frame. This is still essentially a street bike. It’s not a race bike at its core.”

Compared to the stiffness of a modern sportsbike, the bagger feels like it’s from another time, but once I got my head around its oddities, it all started to make sense—somewhat.

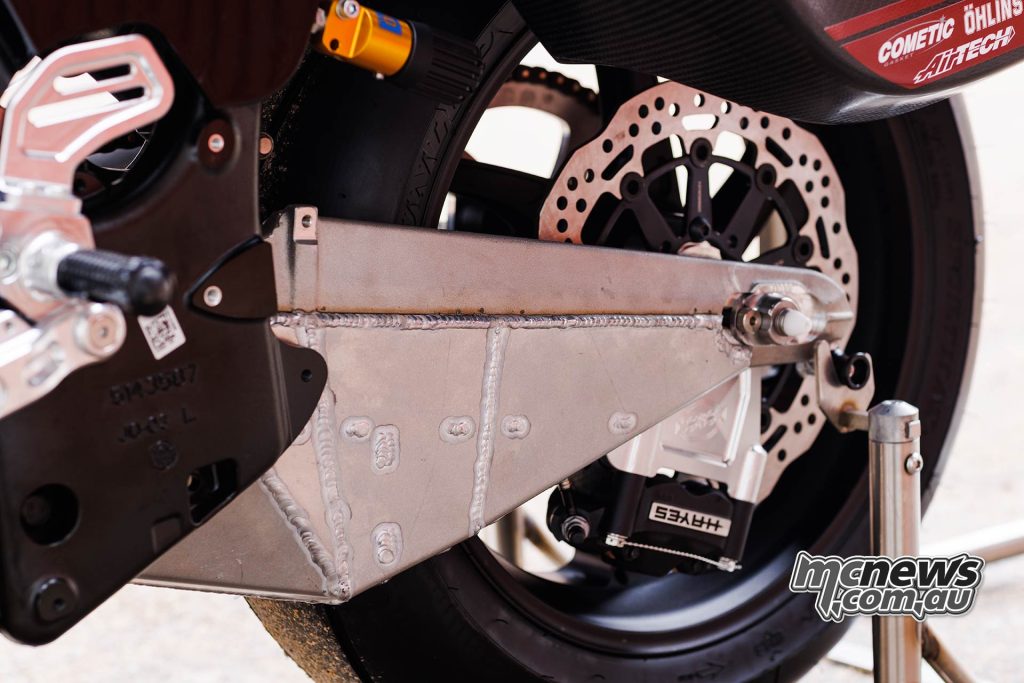

Running Brembo’s billet race caliper, a Galespeed 19 x 19 master-cylinder, a 17 x 6-inch rear and 17 x 3.5-inch front wheel, and modified Ducati Multistrada 1260 Pikes Peak 48mm Ohlins forks, the braking capabilities and turn speed of O’Hara’s bagger are immense.

It’s so long with its lengthened and braced swingarm, and so tall and heavy, that you can absolutely bury the front end under brakes.

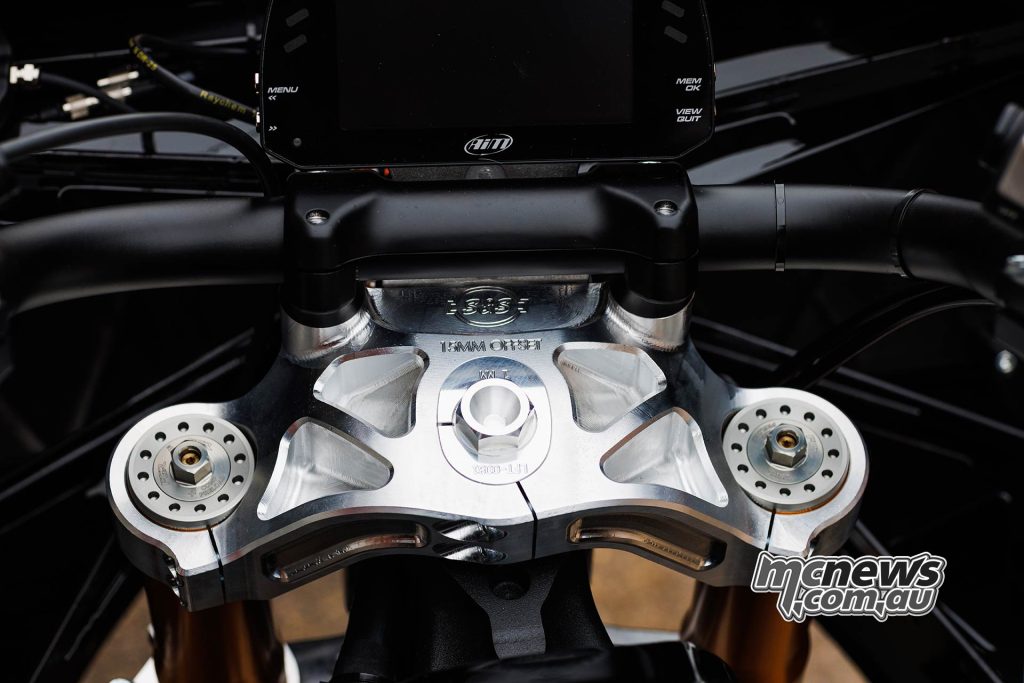

It’s like a superbike style taken to extremes—you brake ultra-late and hard, blow past where you think you should turn, wait a bit, then slam it on its side, pick it up at your earliest convenience, hold the chassis on the rear brake and pull on the noise tube and let that S&S engine roar its brains out towards its 7700 rpm redline on the AiM DL2 dash and datalogger. It’s like riding on a lion chasing its next meal.

The factory Mission Foods/S&S Cycle/Indian Challenger team of Tyler O’Hara and our favourite globetrotting Northern Irishman, Jeremy McWilliams, is not a single entity but a collaboration of Polaris’ (Indian Motorcycle’s parent company) commercial might and legendary tuning house S&S’s expertise.

Unlike arch-rivals Harley Davidson with former champion Kyle Wyman and brother Travis on board, the H-D program is run entirely in house, which is something you can do when you have a labour force (and budget) roughly four times the size of Indian’s.

To create O’Hara’s and McWilliams’s racers, S&S start with a bog-stock Challenger and rip into it. Custom parts from S&S include adjustable triple clamps, a billet front axle, totally revised induction system, billet clutch clover, rearsets, handlebar, rear axle, bellypan and few more bits and bobs like the Saddlemen-made carbon-fibre seat unit and, of course, sidebags, but the engine, obviously, is where much of the attention is paid.

“We’re really focused a lot on airflow,” says Bailey. “It’s mainly all top-end work: we create the camshafts, CNC-machined cylinder heads, and the 110 mm big bore pistons. We machined some rocker arms, too, just for the higher rpm limit. All four rocker arms are different and machined out of a solid chunk of steel. The intake manifold on these bikes is actually 3D-printed aluminum, which is kind of cool, and then the outer runner is plastic, and this joins up to the massive single 78 mm throttle body we took from a Chevy V6 car motor that replaces the twin throttle body set-up of the stock motor.”

Despite my pestering and possible bribing, Neil refused to divulge any performance figures from this monster motor. Boo.

A lightened crank of unspecified weight, allowed by the rules in 2022 but which in 2023 has been mandated at only a 10 per cent weight reduction over stock, helps this V-twin motor spin up with the kind of velocity many V-twin cruiser owners would kill for.

But, like any bike with tons of torque, the game is not so much unleashing it as it is harnessing it. That’s why Jeremy McWilliams was brought on board at the start of 2022 to help the crew work the UK-designed Max ECU’s throttle maps before Daytona.

“Jumping on the bike, it was a real wake-up call because it was the very first kind of roll-out they’ve had on it with all of this extra horsepower and torque compared to the 2021 bike,” McWilliams said. “We didn’t even have a throttle map. We were just running one-to-one. So, jumping on this with a one-to-one throttle map was quite an eye-opener, to say the least.

“We worked closely with the calibration guys. They quickly got a handle on how to transfer all that torque to the rear tyre. Then over the day, we made such big steps that I kind of wanted to come back and do some more.”

Jeremy’s feedback enabled Indian’s technicians to pull the kind of performance out of the bike they’d needed after Kyle Wyman and Harley-Davidson pulled a roundhouse kick on them during the 2021 season.

McWilliams was subsequently hired not just for the season opener at Daytona but for the rest of the year and this year. His take on riding a bagger had me laughing hard in the media room.

“You know what happens when you ride this? You think you’ve mastered it,” he says. “You come back from putting it on the podium, go home, come back a week later and you go, “I know this bike. I know how I finished on it two weeks ago, I’m just going to fit straight back into it.” And you don’t. You can’t go fast until the bike starts to come to you. You don’t just get on and go, “All right, I’m good to go.”

“After a session, then it starts to come to you, but you’re continually tweaking and messing with it, instead of just getting on and trying to ride it. You’re like, “What have I changed? Or what have they changed? What’s going on?” It can mess with your head.”

It can mess with your head just watching these things in action. I was at Daytona for the first round last year and watched McWilliams and Co. head onto the first banking, the one where instead of hitting it at full speed, you’re constantly accelerating and thus putting all those forces through the chassis.

You know when you see a supersport bike doing 200 km/h, it looks like it’s going 200 km/h. It looks like it’s supposed to go 200 km/h.

When you see a bagger doing 200 km/h, especially one on a 37-degree banking like Daytona’s, it looks like it’s going 400 km/h. It snakes and skims its way around the banking while producing a sound that genuinely reminded me of being at Bathurst doing the ’90s when Craig Lowndes was barely out of nappies and kicking everyone’s arse. It sent shivers down my spine. I’ve been to countless MotoGP races and seen the gods ride, but that first glimpse of a bagger doing its thing at Daytona will stay with me forever.

As will those five brief but memorable laps at my local track that I may as well have never ridden before.

O’Hara’s bagger requires a more finely tuned riding style than even a Manx Norton to get the most out of, and to see that he, Wyman, McWilliams and the rest can pull lap-times within five-seconds of Jake Gagne on a WorldSBK Yamaha YZF-R1M at Laguna Seca tells you that although they seem goofy, bulbus, and heavy, these are serious racing machines ridden by riders with balls so big they need wheelbarrows to get around.